What If the Costs Become Untenable? Rethinking SBP’s Monetary Stance

- Muhammad Adil Mansoor

- Economic Advisory Group

EAG Brief | Monetary Policy and Macroeconomic Management

What If the Costs Become Untenable? Rethinking SBP’s Monetary Stance

Muhammad Adil Mansoor, Economic Advisory Group

02-Aug-2025

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The State Bank of Pakistan has made its position clear. It will not cut policy rates unless Islamabad delivers tangible progress on structural reforms. This marks a deliberate shift from strategic ambiguity to a more explicit stance: monetary easing without fiscal discipline is a dead end.

The clarity is welcome. But the posture now carries rising costs. SBP is no longer acting solely as a monetary authority. It is functioning as a macroeconomic shock absorber, a reform enforcer, and a de facto policy anchor. In Pakistan’s ongoing policy vacuum, it has little choice but to hold the line. But the longer it holds, the more fragile that line becomes. Markets may applaud restraint for now, but when restraint becomes inertia, credibility may be on the line.

Without a clearly communicated terminal [policy] rate or a path toward it, uncertainty will continue to paralyze private investment and consumption. Worse, fiscal authorities may respond with distortionary stimulus, off-budget spending, or political quick fixes that aggravate macroeconomic vulnerabilities. The likely outcome: a stalled recovery, escalating political pressure, and a slide back into the very imbalances SBP seeks to correct. This is no longer a question of whether the stance is logical. It is a question of whether it is durable.

This trap is not of SBP’s making. It stems from a broader institutional equilibrium in which all choices appear suboptimal. The central bank’s discipline, however principled, now sits at odds with structural dysfunctions beyond its control. This Brief maps the contradictions and weighs the cost of maintaining the current stance in the absence of reform.

This is no longer a debate about coherence. It is a test of policy sustainability. If SBP continues to shoulder the burden of macroeconomic adjustment alone, the result may not be stability; it may be stasis. Monetary rigidity cannot become a substitute for structural paralysis.

The longer the burden is misallocated, the deeper Pakistan risks slipping into a low growth and high-cost equilibrium. One that punishes formal credit, deters private investment, and invites even riskier forms of state intervention.

POLICY CROSSROADS: WHEN CLARITY MEETS CONTRADICTION

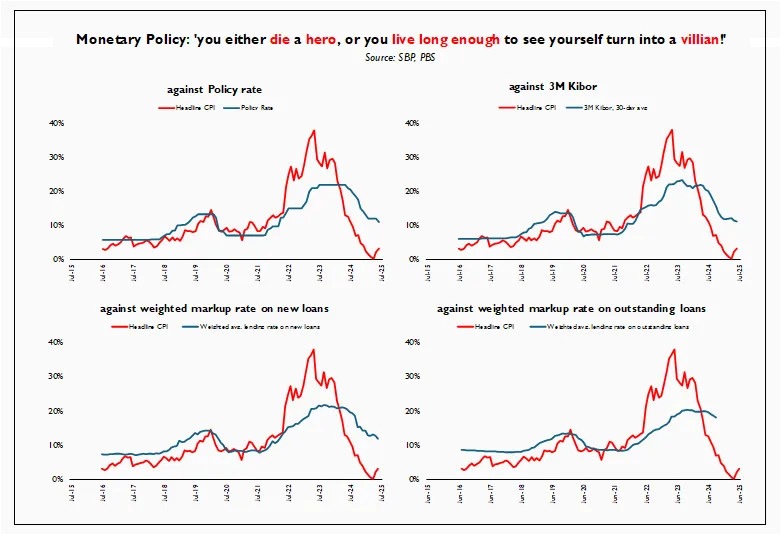

The SBP’s latest MPC statement has dropped all ambiguity. There will be no easing until the government steps up. But this conviction now appears increasingly disconnected from monetary fundamentals.

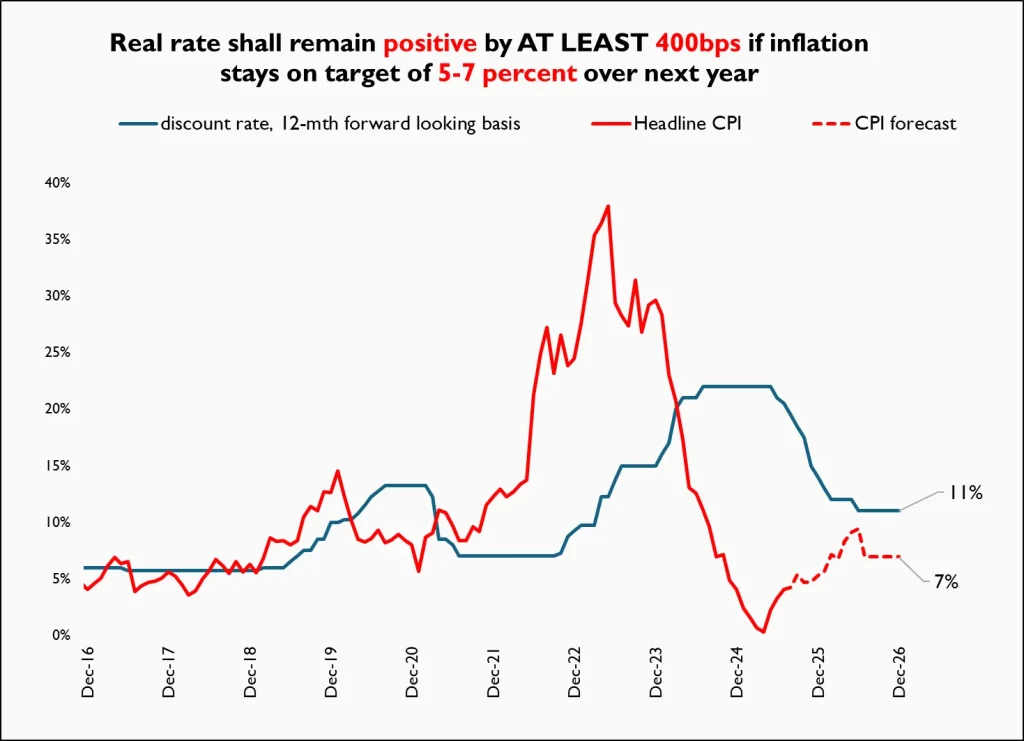

Inflation, according to SBP’s latest forecast, is expected to remain within the medium-term target range of 5 to 7 percent for the current fiscal year. Meanwhile, liquidity conditions remain loose. Reserve money (M0) is growing by over 13 percent year on year, while broad money (M2) is not far behind at 12 percent (average for Jan 2025 to date). And yet:

- The nominal policy rate remains at 11 percent.

- This implies a real interest rate well above both the natural rate of interest and SBP’s own GDP growth forecast.

- Private credit remains stagnant, and investment is flat.

This is not macroprudence. It is policy misalignment. By keeping real rates well above growth expectations, SBP risks locking the economy into a perpetual consolidation trap with no credible off-ramp. If SBP believes its inflation forecast, it must begin adjusting rates in line with it. If it does not, it must say so. Forward guidance cannot coexist with conflicting signals. Policy credibility demands consistency, not silence.

OVERSHOOTS AND MISSING ANCHORS

A second imbalance is emerging. Base money growth is now outpacing nominal GDP.

Assuming nominal GDP growth of 10 percent (4 percent real and 6 percent inflation), monetary aggregates growing at 12 to 13 percent are misaligned. Without tighter reserve money management or a pickup in velocity, inflationary pressures will return regardless of the policy rate.

This is already visible. SBP has injected significant rupee liquidity through FX purchases in the interbank market, driven by a surge in remittances. But this money is not translating into higher output or employment. When money expands faster than income, inflation is not a possibility. It is a delayed inevitability.

FISCAL FALLOUT: WHEN PASSIVITY BREEDS POPULISM

Tight monetary policy does not operate in a vacuum. If growth remains sluggish and private investment remains frozen, fiscal authorities face pressure to act, even if the instruments used are distortionary.

In the absence of structural reform, populist stimuli are re-emerging:

- Markup-free agricultural loans

- Housing concessions

- EV grants and giveaways

They are not reforms. They are reflexes. And they are inflationary. If SBP remains orthodox while the government pursues ad hoc concessions, policy coordination breaks down. Monetary credibility cannot survive fiscal short-termism.

THE BURDEN AND THE BOUNDARY: HOW LONG CAN SBP STAND ALONE?

The SBP’s stance was initially defensible. It was a principled signal to creditors, markets, and Islamabad. But in the absence of structural movement, it is no longer self-evidently sustainable. The central bank is being forced into a corner where its only tools are blunt, and its allies are absent. What began as a policy signal is now morphing into institutional gridlock.

If liquidity continues to expand without productive absorption, if fiscal populism accelerates, and if the private sector remains paralyzed, the SBP will eventually face a binary choice: reverse course under pressure or accept the cost of prolonged stagflation. Either path carries institutional risk.

This trap is not of SBP’s making. It is the product of a vacuum where the primary actors in Islamabad have abdicated reform. But if SBP does not clearly articulate the limits of its mandate, it risks becoming the face of a broader failure it does not control. The longer that vacuum persists, the greater the risk that SBP becomes not just the shock absorber, but the scapegoat.

Even if one remains skeptical of SBP’s inflation outlook and sees upside risks to price levels or currency volatility, the real rate gap remains significant. If the current policy stance is driven by concerns beyond inflation, such as FX stability or debt rollover risks, that rationale must be clearly communicated. Otherwise, forward guidance collapses into opacity.

SBP must protect its credibility not just by holding the line, but by defining where the line ends, and where other institutions must step in. If neither Karachi recalibrates nor Islamabad reforms, Pakistan may end up with the worst of both worlds: no growth, no credibility, and no macro policy room left to maneuver. A liquidity trap from below, a credibility trap from above.

WAY FORWARD

- Signal a Terminal Rate: Without forward guidance, investment and credit planning remain frozen. A medium-term nominal interest rate target, for instance, at 9 percent, would help anchor expectations and support recalibration.

- Call Out the Contradiction: If real policy rates are targeting 4 to 5 percent while expected growth is 3 to 4 percent, SBP is not done tightening. It must say so clearly or adjust the rate.

- Watch Base Money Growth: With M0 and M2 expanding faster than nominal GDP, aggregate monetary conditions are no longer neutral. SBP must reconcile its policy stance with its balance sheet dynamics and FX operations.

- Institutionalize Shared Accountability: Monetary discipline must be matched by fiscal reform. SBP’s Research department should publish an institutional benchmark and an inflation-consistent fiscal path to clarify the tradeoffs it is carrying alone.

- Activate Credit Through Formal Channels: Idle liquidity must be deployed productively. SBP should scale up risk-sharing facilities, credit guarantee programs, and regulated credit enhancements, rather than allow fiscal authorities to crowd out private commercial lending through unsustainable subsidies.

FINAL WORD

The SBP drew a principled line. But that line now risks cracking under the weight of structural inertia beyond its control. Base money is growing faster than output. Real interest rates are stifling investment. Fiscal stimulus is drifting back into distortion. The question now is not whether SBP is right. It is how long it can remain alone.

If Islamabad does not move, the burden will fall entirely on Karachi. And the longer the delay in recalibration, the higher the eventual costs. Not in basis points, but in growth lost, inflation reignited, and institutional credibility eroded.

The cost of discipline without reform is becoming untenable.